#1 Mustaches

BABBUZ | Brooch | Felt and silk wire | 2009

LUDWIG | Necklace | Silver and ribbon | 2010

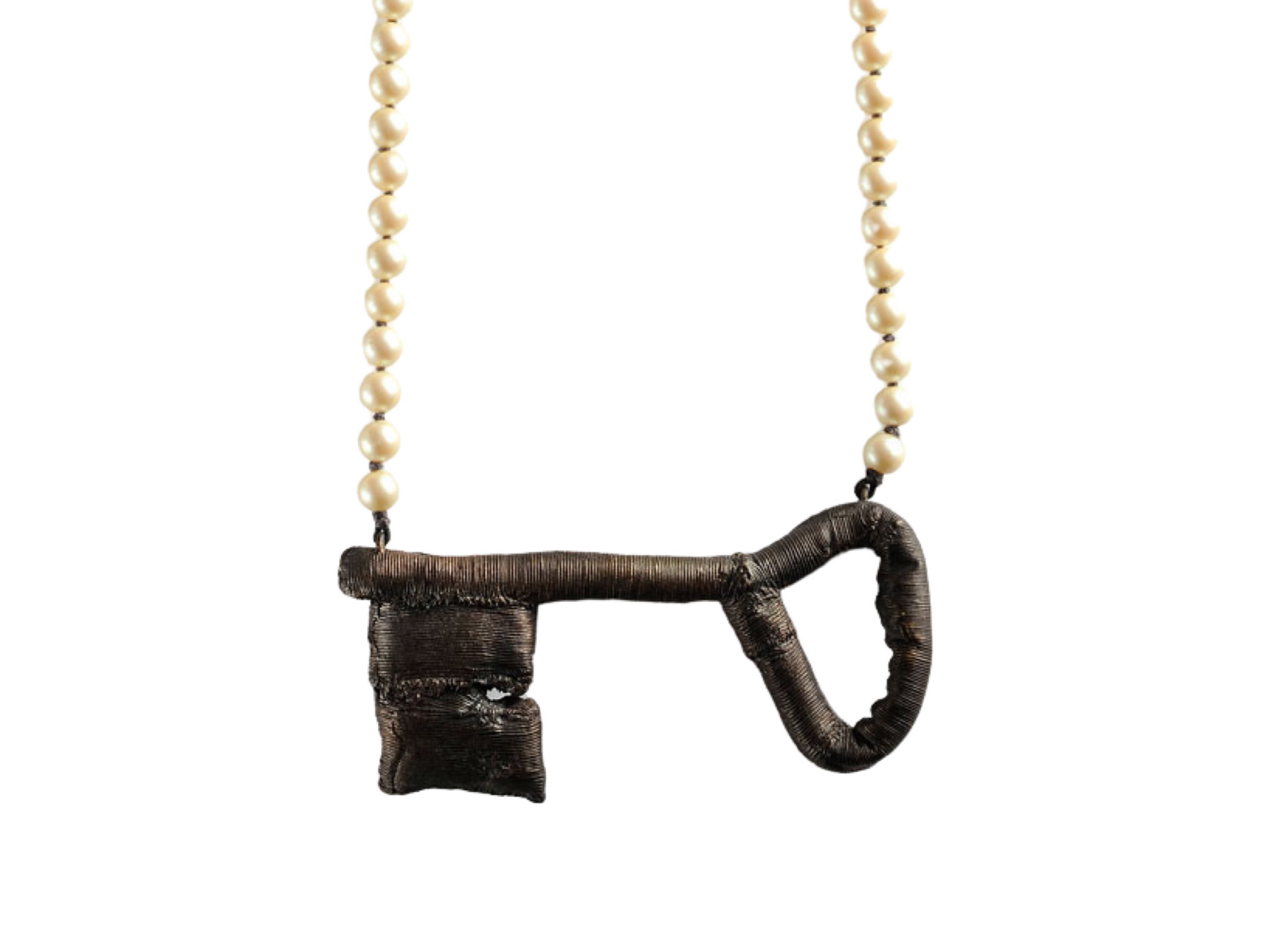

MONSIEUR GASTON | Necklace | Textile, gold 18kt, pearls, resin | 2010

PABLITO EL DRITO | Necklace | Silver and silk wire | 2010

MANGIAFUOCO | Necklace | Silicon, resin and silver | 2010

Alfiero as 'Ludwig'

Sandy Bar, via dell'Orto, Florence.

On the 28th of May, 2010, Saturday morning.

LUDWIG

Dopo aver dato le ultime disposizioni si sdraiò sulla branda e dopo poco prese sonno, un sonno senza sogni.

L’indomani tutto era pronto. La mattina era fredda e senza sole, un vento gelido spazzava il campo dove cominciavano ad adunarsi i reparti. Ufficiali a cavallo andavano e venivano portando ordini e passando in rassegna le truppe. Tutto si svolgeva con estrema precisione e maniacale attenzione ai dettagli.

Dentro la sua tenda, il comandante Ludwig von Falkenhayn aspettava la battaglia. I suoi pensieri furono interrotti dall’arrivo del suo attendente il quale annunciò che la brigata era pronta a muoversi.

Ludwig controllò un’ultima volta la divisa e le armi e per un attimo fu pervaso da una strana malinconia che scacciò subito dal cuore. Prese del grasso con cui si spalmò i baffi per renderli rigidi e sottili come lame, impugnò l’elsa della spada e uscì dalla tenda.

After giving his last disposition he lied down on the camp-bed and he fell asleep, a sleep without dreams.

The day after it was all ready. The morning was cold and without sun and there was a freezing wind in the camp where the units started to assemble. The officers went to and fro giving orders and checking the units. All was run with extreme precision and mechanical attention to detail.

In his tent, the commander Ludwig von Falkenhayn waited for battle. His thoughts were interrupted by the arrival of his orderly, who announced that the brigade was ready to move.

Ludwig checked his uniform and the weapons for the last time and for a brief moment he felt a strange sense of melancholy but he immediately expelled it from his heart. He took some grease to make his moustache stiff and thin like blades, then grasped the hilt of his sword and left the tent.

The day after it was all ready. The morning was cold and without sun and there was a freezing wind in the camp where the units started to assemble. The officers went to and fro giving orders and checking the units. All was run with extreme precision and mechanical attention to detail.

In his tent, the commander Ludwig von Falkenhayn waited for battle. His thoughts were interrupted by the arrival of his orderly, who announced that the brigade was ready to move.

Ludwig checked his uniform and the weapons for the last time and for a brief moment he felt a strange sense of melancholy but he immediately expelled it from his heart. He took some grease to make his moustache stiff and thin like blades, then grasped the hilt of his sword and left the tent.

Mr. Eugenio as 'Monsieur Gaston'

in the living room of his house.

On the 14th of June, 2010.

MONSIEUR GASTON

Quando cucinava sembrava un pittore al lavoro. Su un tavolo c’era il pesce o la carne e tutt’intorno vari intingoli e salse, proprio come i colori di una tavolozza. Realizzava le sue opere davanti agli ospiti, spiegando come fare e ordinando l’apertura di bottiglie di vino.

Gaston Dugrail o Monsieur Gaston, come lo chiamava mio padre, era il suo socio in affari e il suo migliore amico. Non si era voluto sposare e non aveva figli, così alla domenica o durante le feste cenava da noi, ma esigeva di cucinare personalmente. A tavola ci raccontava dei suoi viaggi in Indocina, dove aveva fatto non si capiva bene quale lavoro.

Si agitava, si scomponeva e si ricomponeva, grosso e grasso e rosso per il vino. La sua voce potente usciva dai folti baffi che giù dagli angoli della bocca gli coprivano le labbra quasi del tutto.

Sfinito si accasciava sul divano. Quello era il segnale che la festa era finita e che mio padre doveva riaccompagnarlo a casa.

Gaston Dugrail o Monsieur Gaston, come lo chiamava mio padre, era il suo socio in affari e il suo migliore amico. Non si era voluto sposare e non aveva figli, così alla domenica o durante le feste cenava da noi, ma esigeva di cucinare personalmente. A tavola ci raccontava dei suoi viaggi in Indocina, dove aveva fatto non si capiva bene quale lavoro.

Si agitava, si scomponeva e si ricomponeva, grosso e grasso e rosso per il vino. La sua voce potente usciva dai folti baffi che giù dagli angoli della bocca gli coprivano le labbra quasi del tutto.

Sfinito si accasciava sul divano. Quello era il segnale che la festa era finita e che mio padre doveva riaccompagnarlo a casa.

When he cooked, he looked like a painter at work. There was fish and meat on the table and sauces and gravies all around, like colours on a palette. He did his work in front of the customers, explaining how to order and open wine bottles.

Gaston Dugrail or Monsieur Gaston, as my father called him, was his business partner and his best friend. He was not married and he didn’t have any family, so on Sundays and during the holidays he ate with us, but he demanded to do the cooking himself. At dinner he told us about his travels in Indochina, where he had an undefined job.

He moved about, restless and fidgety; big, fat and red from the wine he drank. His strong voice boomed out from his big moustache that almost totally covered his lips.

Exhausted, he lay down on the sofa. That was the signal that the feast was over and my father had to take him home.

Gaston Dugrail or Monsieur Gaston, as my father called him, was his business partner and his best friend. He was not married and he didn’t have any family, so on Sundays and during the holidays he ate with us, but he demanded to do the cooking himself. At dinner he told us about his travels in Indochina, where he had an undefined job.

He moved about, restless and fidgety; big, fat and red from the wine he drank. His strong voice boomed out from his big moustache that almost totally covered his lips.

Exhausted, he lay down on the sofa. That was the signal that the feast was over and my father had to take him home.

Vittorio from his second-hand shop as ' Pablito el Drito'

Via di S. Monaca (?), Florence.

September 2010, appointment at noon.

September 2010, appointment at noon.

PABLITO EL DRITO

You don’t have to search in the rich European clubs or in stadiums for one hundred thousand people, the essence of soccer is in the smaller clubs, in the suburbs and towns. There you will find El Drito, Pablo, Pablito, like lightning, poor and thin like a rail. The only ornament is his blonde moustache, the same as his Norman father, the only thing someone gave him.

El Drito runs with determination on the ground; he has no fear of anyone nor of himself.

Come see him play one day. It’s marvellous when he springs in a cloud of dust, jumps the defender, enters the goal area and beats the goalkeeper.

You’ll recognize him from his hair, long and red, that dances with the shaking of his head, while the crowd screams with tears in their eyes.

Non devi cercare nei ricchi club europei e neanche negli stadi da centomila posti, l’essenza del calcio è nelle serie minori, nelle periferie e nei piccoli paesi. E’ lì che lo troverai, el Drito, Pablo, Pablito, il fulmine, povero in canna e magro come un chiodo. L’unico ornamento che porta sono i suoi baffi biondi, che poi sono gli stessi che aveva il padre normanno, l’unica cosa che qualcuno gli abbia mai regalato.

El Drito corre a testa alta nel campo, non ha paura di nessuno, neanche di se stesso.

Vieni a vederlo un giorno. E’ una meraviglia quando scatta in una nuvola di polvere, salta il difensore, entra in area e brucia il portiere.

Lo riconoscerai dai capelli, quei lunghi capelli rossi che ballano con lui sbattendogli sul collo, mentre la gente grida, mentre la gente ha le lacrime agli occhi.

El Drito corre a testa alta nel campo, non ha paura di nessuno, neanche di se stesso.

Vieni a vederlo un giorno. E’ una meraviglia quando scatta in una nuvola di polvere, salta il difensore, entra in area e brucia il portiere.

Lo riconoscerai dai capelli, quei lunghi capelli rossi che ballano con lui sbattendogli sul collo, mentre la gente grida, mentre la gente ha le lacrime agli occhi.

You don’t have to search in the rich European clubs or in stadiums for one hundred thousand people, the essence of soccer is in the smaller clubs, in the suburbs and towns. There you will find El Drito, Pablo, Pablito, like lightning, poor and thin like a rail. The only ornament is his blonde moustache, the same as his Norman father, the only thing someone gave him.

El Drito runs with determination on the ground; he has no fear of anyone nor of himself.

Come see him play one day. It’s marvellous when he springs in a cloud of dust, jumps the defender, enters the goal area and beats the goalkeeper.

You’ll recognize him from his hair, long and red, that dances with the shaking of his head, while the crowd screams with tears in their eyes.

My father as 'The Fire Eater'

on the terrace of his house in Florence.

April 2010, early afternoon.

THE FIRE EATER

for S.T. Coleridge

for S.T. Coleridge

Sono in ritardo, come sempre. Mi devo ancora fare il nodo alla cravatta e poi dov’è la chiesa? Qual è la strada? Ecco, ci sono, lo sposo è fuori sul sagrato che aspetta.

Mi ferma un vecchio, mi afferra per un braccio, stringe parecchio. Mi invita a sedere su una pietra, nel suo sguardo brucia la mia immagine riflessa.

Il suo occhio sfavillante mi blocca, mi trattiene. Dimentico il matrimonio e siedo accanto a lui, vecchio e stanco, con la barba grigia aggrappata a un viso segnato da una vita intera.

E’ stato marinaio, ha visto tutti gli oceani e attraversato tutto il mondo, giù nelle caldaie, spalando il carbone. “Sembra di dare da mangiare ad una bestia feroce”. I suoi baffi sono stati neri e forti e spavaldi in quei giorni.

Mi racconta l’orrore, il naufragio, il dolore che si prova quando la nave affonda: “Il mare è cattivo, ragazzo, ha sempre fame”.

Dalla chiesa si sentono i canti, escono gli sposi nella sera del loro primo giorno.

Mi ferma un vecchio, mi afferra per un braccio, stringe parecchio. Mi invita a sedere su una pietra, nel suo sguardo brucia la mia immagine riflessa.

Il suo occhio sfavillante mi blocca, mi trattiene. Dimentico il matrimonio e siedo accanto a lui, vecchio e stanco, con la barba grigia aggrappata a un viso segnato da una vita intera.

E’ stato marinaio, ha visto tutti gli oceani e attraversato tutto il mondo, giù nelle caldaie, spalando il carbone. “Sembra di dare da mangiare ad una bestia feroce”. I suoi baffi sono stati neri e forti e spavaldi in quei giorni.

Mi racconta l’orrore, il naufragio, il dolore che si prova quando la nave affonda: “Il mare è cattivo, ragazzo, ha sempre fame”.

Dalla chiesa si sentono i canti, escono gli sposi nella sera del loro primo giorno.

I’m late as usual. I still have to tie the knot of my tie. Where is the church? Where is the street? Well, I’m finally here. The bride is waiting in the churchyard.

An old man stops me, grabs me by the arm, clutches me tightly. He invites me to sit on a stone, my reflected imagine burns in his eyes.

His sparkling eye holds me. I forget the wedding as I sit beside him, old and tired with his grey beard on a face marked by a long life.

He was a sailor; he saw all the oceans he had crossed all over the world, shovelling coal into the ships boilers. "It seems to feed a wild beast". His moustache was black, strong and arrogant during these days. He tells me about the horror, the shipwreck, the pain he felt when a ship sank. "The sea is bad, my boy. It’s always hungry".

From the church I can hear the chants. The bride and the groom go out into the evening of their first day of married life together.

Stories are by Pietro Guiso, translations by Maria Elena Manzo and Geraldine Nishi.

Prpject, photos and art jewels by Eugenia Ingegno.